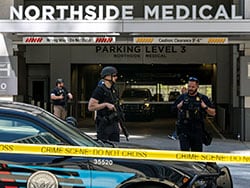

Two fatal hospital shootings in May — one in Virginia that left one co-worker dead and another in Atlanta that left one patient dead and four other patients injured — have doctors questioning how safe their workplaces are and how they should handle a potential threat.

This comes amid rising physician injuries and deaths from acute care hospital shootings. These have more than tripled during the past two decades, according to a recent study.

Although medical buildings have policies or signs banning firearms inside their buildings, that hasn’t deterred some gun owners from bringing their weapons into their doctors’ offices. When that happens, doctors can do simple things to prevent a potentially dangerous situation from becoming worse, says Kenneth Cheng, DO, a family physician and reserve deputy sheriff based in Southern California.

Here’s 3 steps to protect yourself.

1. Do not turn your back to the patient. Cheng was on-call at a local hospital when a nurse told him that a patient needing evaluation hated Asians. “I talked to him about whether he was okay seeing me and he said yes,” Cheng said. “But I remained vigilant and conscious of what the patient was doing the whole time so he couldn’t take advantage of the situation.”

Cheng never turned his back to the patient and even backed out of the exam room. That encounter passed without incident.

2. Look at the person’s body language for signs of increasing agitation or tension, such as clenched fists, tense posture, tight jaw, or fidgeting that may be accompanied by shouting and/or verbal abuse.

“Certainly, if the patient is belligerent of threatening, a call to security is warranted,” said Cheng. However, if they are of low or no suspicion, a judgment call can be made as to whether to continue with the exam or to ask them to return to their vehicle to safely store the firearm and then return for their exam, he said.

Jacqui O’Kane, DO, a family physician at South Georgia Medical Center in Nashville, Georgia, decided to continue an examination after a new patient in his late 20s told her that he didn’t like his previous doctor and had shown his gun to him. “Then the patient pulled his shirt up to reveal the holster to me. He reassured me, ‘But don’t worry, I like you — so far,’ ” said O’Kane.

“I froze with fear in that moment, afraid that if I said or typed anything, I could set him off,” she said. Once he changed the subject and seemed less hostile, she typed a message to her medical assistant saying, “He has a gun.” She offered to call 911. O’Kane responded, “No. Not threatening. Just FYI.”

3. Consider where you are physically in relation to patients in the exam room. “You don’t want to be too close to the patient or stand in front of them, which can be seen as confrontational. Instead, stand or sit off to the side, and never block the door if the patient is upset,” said Cheng.

Board-certified internist Theresa Rohr-Kirchgraber, MD, was working at an outpatient office in Indianapolis, when her new 39-year-old male patient told her that he was carrying a gun.

“It can be very disconcerting to have an uncomfortable conversation with a patient in a small exam room. I am only 5 feet tall and he was towering over me,” said Rohr-Kirchgraber, a professor of medicine at Augusta University/University of Georgia Medical Partnership.

She told the gun owner that her office didn’t allows guns inside. Although she eventually persuaded him to take the gun off and put it to the side during the exam, she said it was unnerving. “It was a very uncomfortable conversation. He wanted pain medications and Adderall from me and he’s wearing his gun — what if I didn’t give it to him — would he shoot me?”

Cheng recommended that doctors not ask patients who are licensed to carry concealed weapons to leave their guns in a different location such as giving it to someone or placing it in another room. “That’s a violation of their CCW (Concealed Carry Weapon) license. They are mandated to always maintain direct control of their firearm,” he said.

Christine Lehmann, MA, is a senior editor and writer for Medscape Business of Medicine based in the Washington, DC area. She has been published in WebMD News, Psychiatric News, and The Washington Post. Contact Christine at [email protected] or via Twitter @writing_health

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn

Source: Read Full Article