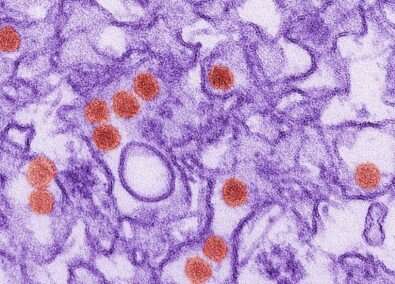

An international group of researchers have discovered that inhibiting AHR (aryl hydrocarbon receptor)—a protein with roles in regulating immunity, stem cell maintenance and cellular differentiation—enables the immune system to combat replication of zika virus in the organism far more effectively. In experiments performed at the University of São Paulo’s Biomedical Sciences Institute (ICB-USP) in Brazil, the antiviral therapy proved capable of preventing the development of microcephaly and other malformations in mouse fetuses whose mothers were infected while pregnant.

The study was supported by FAPESP. An article describing the results was published on July 20 in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

“In the experiments, we used an experimental drug that inhibits AHR and observed a decrease in replication of both zika virus and dengue virus. We now plan to test the effectiveness of the therapy against the novel coronavirus,” said Jean Pierre Peron, a professor at ICB-USP and co-principal investigator for the project alongside Cybele Garcia, a virologist at the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina, and Francisco Quintana, a professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School in the United States.

The experimental model used in the study was the same as that used by Peron’s group in 2016 to prove a causal link between zika virus and microcephaly. On that occasion, female mice of the SJL strain, which are much more susceptible to zika infection than other laboratory animals, were infected with the virus between the tenth and twelfth day of pregnancy. When the pups were born, the researchers found a significant reduction in cortical layer thickness, as well as alterations in the number and morphology of cortical and other brain cells. They also found that the virus replicated far more rapidly in placenta and in the pups’ brains than in other organs.

“We repeated this experiment with a difference,” Peron said. “Shortly before we infected the pregnant females with zika, we began orally administering the AHR inhibitor. The treatment continued until the end of the gestational period. The pups had normal brains in terms of size and weight, and a far lower viral load than the non-treated control group. Viral load was almost undetectable in both the placenta and the central nervous system. In addition, histopathological analysis showed that there was no reduction in cortical layer thickness and that the number of nervous system cells killed by the virus was much smaller.”

According to Peron, no adverse effects were observed in the mice treated with the AHR inhibitor, but before the treatment is tested in human volunteers the experiment must be replicated in monkeys.

The study took four years to be completed. Nagela Zanluqui and Carolina Polonio, both Ph.D. candidates at ICB-USP with scholarships from FAPESP, also participated.

Inception

Quintana’s laboratory at Harvard is one of the world’s leading centers in studies of the protein AHR. In an interview given to Agência FAPESP, Quintana said his group discovered some years ago that interferons, proteins produced by immune cells in the inflammatory response to infections, control the activation of AHR.

“Because interferons are central to the antiviral immune response, we postulated—together with Garcia’s group—that AHR might be involved in the suppression of immunity against viruses. We designed anti-AHR therapies and developed nanoparticles and inhibitors for use in the experiments,” Quintana said.

Tests performed in the laboratory and in animals confirmed that viruses activate AHR to suppress the host’s immune response. This may occur when a pathogen infects the liver, triggering release of the tryptophan metabolite kynurenine.

“This metabolite activates AHR, which inhibits the expression of another protein called PML [promyelocytic leukemia protein]—very important to the antiviral immune response—and thereby lets the virus replicate more freely in cells,” Peron said.

At the University of Buenos Aires, Garcia led experiments with various cell lines including hepatocytes and neural progenitors, stem cells that have the capacity to differentiate into neuronal and glial cells.

“We treated the cell lines with AHR agonist compounds [which magnify the action of the protein] and AHR antagonists [which inhibit it],” Garcia told Agência FAPESP. “In this manner we confirmed that negative modulation of this receptor inhibits replication of zika. In the same way we demonstrated that positive modulation boosts viral replication in cells.”

Environmental factors

The impact of the 2015 zika epidemic was highly asymmetrical, Garcia said. In some regions and cities, the incidence of the congenital syndrome and microcephaly caused by the virus was much higher than in others. In her view this may be because of environmental factors favoring infection in the worst-hit areas or because their inhabitants were more susceptible. Both factors may also have contributed simultaneously to an intensification of zika’s impact.

Source: Read Full Article