Dr Chris Nowinski

On October 5, 2022 at 10:24 am, Chris Nowinski, PhD, co-founder of the Boston-based Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF), was in his home office when the email came through. For the first time, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) acknowledged there was a causal link between repeated blows to the head and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

“I pounded my desk, shouted YES! and went to find my wife so I could pick her up and give her a big hug,” he recalls. “It was the culmination of 15 years of research and hard work.”

Robert Cantu, MD, who has been studying head trauma for 50+ years and has published over 500 papers about it, compares the announcement to the 1964 Surgeon General’s report that linked cigarette smoking with lung cancer and heart disease. With the NIH and the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now in agreement about the risks of participating in impact sports and activities, he says, “We’ve reached a tipping point that should finally prompt deniers such as the NHL, NCAA, FIFA, World Rugby, the International Olympic Committee, and other [sports organizations] to remove all unnecessary head trauma from their sports.”

“A lot of the credit for this must go to Chris,” adds Cantu, the medical director and director of clinical research at the Cantu Concussion Center at Emerson Hospital in Concord, Massachusetts. “Clinicians like myself can reach only so many people by writing papers and giving speeches at medical conferences. For this to happen, the message needed to get out to parents, athletes, and society in general. And Chris was the vehicle for doing that.”

Nowinski didn’t set out to be the messenger. He played football at Harvard in the late 1990s, making second-team All-Ivy as a defensive tackle his senior year. In 2000, he enrolled in Killer Kowalski’s Wrestling Institute and eventually joined Vince McMahon’s World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE).

There he played the role of 295-pound villain “Chris Harvard,” an intellectual snob who dressed in crimson tights and insulted the crowd’s IQ. “Roses are red. Violets are blue. The reason I’m talking so slowly is because no one in [insert name of town he was appearing in] has passed Grade 2!”

“I’d often apply my education during a match,” he writes in his book Head Games: Football’s Concussion Crisis. “In a match in Bridgeport, Connecticut, I assaulted [my opponent] with a human skeleton, ripped off the skull, got down on bended knee, and began reciting Hamlet. Those were good times.”

Those good times ended abruptly, however, during a match with Bubba Ray Dudley at the Hartford Civic Center in Connecticut in 2003. Even though pro wrestling matches are rehearsed, and the blows aren’t real, accidents happen. Dudley mistakenly kicked Nowinski in the jaw with enough force to put him on his back and make the whole ring shake.

“Holy shit, kid! You okay?” asked the referee. Before a foggy Nowinski could reply, 300-pound Dudley crashed down on him, hooked his leg, and the ref began counting, “One! Two! …” Nowinski instinctively kicked out but had forgotten the rest of the script. He managed to finish the match and stagger backstage.

His coherence and awareness gradually returned, but a “throbbing headache” persisted. A locker room doctor said he might have a concussion and recommended he wait to see how he felt before wrestling in Albany, New York, the next evening.

The following day the headache had subsided, but he still felt “a little strange.” Nonetheless, he told the doctor he was fine and strutted out to again battle Bubba Ray, this time in a match where he eventually got thrown through a ringside table and suffered the Dudley Death Drop. Afterward, “I crawled backstage and laid down. The headache was much, much worse.”

An Event and a Process

Nowinski continued to insist he was “fine” and wrestled a few more matches in the following days before finally acknowledging something was wrong. He’d had his bell rung numerous times in football, but this was different. Even more worrisome, none of the doctors he consulted could give him any definitive answers. He finally found his way to Emerson Hospital, where Cantu was the chief of neurosurgery.

“I remember that day vividly,” says Cantu. “Chris was this big, strapping, handsome guy — a helluva athlete whose star was rising. He didn’t realize that he’d suffered a series of concussions and that trying to push through them was the worst thing he could be doing.”

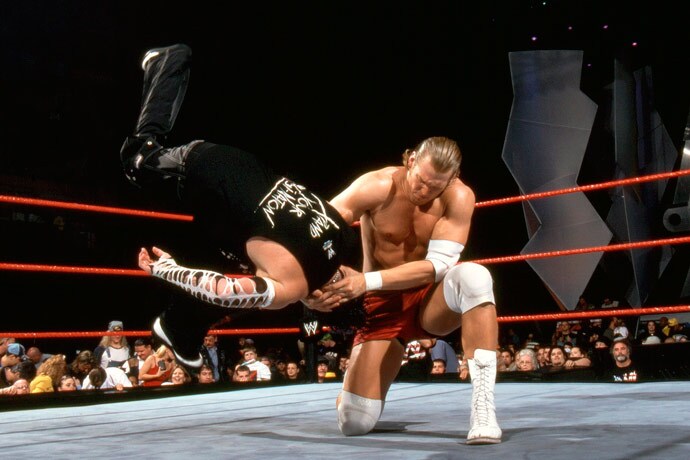

Chris Nowinski wrestled in the WWE as 295-pound villain “Chris Harvard” until a kick to the head in 2003 left him with a concussion and ultimately forced him out of the ring.

Concussions and their effects were misunderstood by many athletes, coaches, and even physicians back then. It was assumed that the quarter inch of bone surrounding the adult brain provided adequate protection from common sports impacts and that any aftereffects were temporary. A common treatment was smelling salts and a pat on the back as the athlete returned to action.

However, the brain floats inside the skull in a bath of cerebral fluid. Any significant impact causes it to slosh violently from side to side, damaging tissue, synapses, and cells resulting in inflammation that can manifest as confusion and brain fog.

“A concussion is actually not defined by a physical injury,” explains Nowinski, “but by a loss of brain function that is induced by trauma. Concussion is not just an event, but also a process.” It’s almost as if the person has suffered a small seizure.

Fortunately, most concussion symptoms resolve within 2 weeks, but in some cases, especially if there’s been additional head trauma, they can persist, causing anxiety, depression, anger, and/or sleep disorders. Known as post-concussion syndrome (PCS), this is what Nowinski was unknowingly suffering from when he consulted Cantu.

In fact, one night it an Indianapolis hotel, weeks after his initial concussion, he awoke to find himself on the floor and the room in shambles. His girlfriend was yelling his name and shaking him. She told him he’d been having a nightmare and had suddenly started screaming and tearing up the room. “I didn’t remember any of it,” he says.

Cantu eventually advised Nowinski against ever returning to the ring or any activity with the risk for head injury. Research shows sustaining a single significant concussion increases the risk of subsequent more-severe brain injuries.

“My diagnosis could have sent Chris off the deep end because he could no longer do what he wanted to do with this life,” says Cantu. “But instead, he used it as a tool to find meaning for his life.”

Nowinski decided to use his experience as a teaching opportunity, not just for other athletes but also for sports organizations and the medical community.

His book, Head Games: Football’s Concussion Crisis, which focused on the NFL’s “tobacco-industry-like refusal to acknowledge the depths of the problem” was published in 2006. A year later, Nowinski partnered with Cantu to found the Sports Legacy Institute, which eventually became the Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF).

Cold Calling for Brain Donations

Robert Stern, PhD, is another highly respected authority in the study of neurodegenerative disease. In 2007, he was directing the clinical core of Boston University’s Alzheimer’s Disease Center. After giving a lecture to a group of financial planners and elder-law attorneys one morning, he got a request for a private meeting from a fellow named Chris Nowinski.

“I’d never heard of him, but I agreed,” recalls Stern, a professor of neurology, neurosurgery, anatomy and neurobiology at Boston University. “A few days later, this larger-than-life guy walked into our conference room at the BU School of Medicine, exuding a great deal of passion, intellect, and determination. He told me his story and then started talking about the long-term consequences of concussions in sports.”

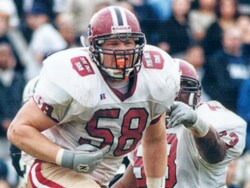

Chris Nowinski played defensive tackle for Harvard in the late ’90s and made second-team All-Ivy as a senior.

Stern had seen patients with dementia pugilistica, the old-school term for CTE. These were mostly boxers with cognitive and behavioral impairment. “But I had not heard about football players,” he says. “I hadn’t put the two together. And as I was listening to Chris, I realized if what he was saying was true then it was not only a potentially huge public health issue, but it was also a potentially huge scientific issue in the field of neurodegenerative disease.”

Nowinski introduced Stern to Cantu, and together with Ann McKee, MD, a professor of neurology and pathology at BU, they co-founded the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy (CSTE) in 2008. It was the first center of its kind devoted to the study of CTE in the world.

One of Nowinski’s first jobs at the CSTE was soliciting and procuring brain donations. Since CTE is generally a progressive condition that can take decades to manifest, autopsy was the only way to detect it.

The brains of two former Pittsburgh Steelers, Mike Webster and Terry Long, had been examined after their untimely deaths. After immunostaining, investigators found both former NFL players had “protein misfolds” characteristic of CTE.

This finding drew a lot of public and scientific attention, given that Long died by suicide and Webster was homeless when he died of a heart attack. But more scientific evidence was needed to prove a causal link between the head trauma and CTE.

Nowinski scoured obituaries looking for potential brains to study. When he found one, he would cold call the family and try to convince them to donate it to science. The first brain he secured for the center belonged to John Grimsley, a former NFL linebacker who in 2008 died at age 45 of an accidental gunshot wound. Often, Nowinski would even be the courier, traveling to pick up the brain after it had been harvested.

Over the next 10 years, Nowinski and his research team secured 500 brain donations. The research that resulted was staggering. In the beginning only 45 cases of CTE had been identified in the world, but in the first 111 NFL players who were autopsied, 110 had the disorder.

Of the first 53 college football players autopsied, 48 had CTE. Although Nowinski’s initial focus was football, evidence of CTE was soon detected among athletes in boxing, hockey, soccer, and rugby, as well as combat veterans. However, the National Football League and other governing sports bodies initially denied any connection between sport-related head trauma and CTE.

Cumulative Damage

In 2017, after 7 years of study, Nowinski earned a PhD in neurology. As the scientific evidence continued to accumulate, two shifts occurred that Stern says represent Nowinski’s greatest contributions. First, concussion is now widely recognized as an acute brain injury with symptoms that need to be immediately diagnosed and addressed.

“This is a completely different story from where things were just 10 years ago,” says Stern, “and Chris played a central role, if not the central role, in raising awareness about that.”

All 50 states and the District of Columbia now have laws regarding sports-related concussion. And there are brain banks in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Brazil and the UK studying CTE. Over 2500 athletes in a variety of sports, including NASCAR’s Dale Earnhardt Jr and NFL hall of famer Nick Buoniconti, have publicly pledged to donate their brains to science after their deaths.

Second, says Stern, we now know that although concussions can contribute to CTE, they are not the sole cause. It’s repetitive sub-concussive trauma, without symptoms of concussion, that do the most damage.

“These happen during every practice and in every game,” says Stern. In fact, it’s estimated that pro football players suffer thousands of sub-concussive incidents over the course of their careers. So, a player doesn’t have to see stars or lose consciousness to suffer brain damage; small impacts can accumulate over time.

Understanding this point is crucial for making youth sports safer. “Chris has played a critical role in raising awareness here too,” says Stern. “Allowing our kids to get hit in the head over and over can put them at greater risk for later problems, plus it just doesn’t make common sense.”

“The biggest misconception surrounding head trauma in sports,” says Nowinski, “is the belief among players, coaches, and even the medical and scientific communities that if you get hit in the head and don’t have any symptoms then you’re okay and there hasn’t been any damage. That couldn’t be further from the truth. We now know that people are suffering serious brain injuries due to the accumulated effect of sub-concussive impacts, and we need to get the word out about that.”

A major initiative from the Concussion Legacy Foundation called “Stop Hitting Kids in the Head” has the goal of convincing every sport to eliminate repetitive head impacts in players under age 14 — the time when the skull and brain are still developing and most vulnerable — by 2026. In fact, Nowinski writes that “there could be a lot of kids who are misdiagnosed and medicated for various behavioral or emotional problems that may actually be head-injury related.”

Starting in 2009, the NFL adopted a series of rule changes designed to better protect its players against repeated head trauma. Among them is a ban on spearing or leading with the helmet, penalties for hitting defenseless players, and more stringent return-to-play guidelines, including concussion protocols.

The NFL has also put more emphasis on flag football options for youngsters and, for the first time, showcased this alternative in the 2023 Pro Bowl. But Nowinski is pressuring the league to go further. “While acknowledging that the game causes CTE, the NFL still underwrites recruiting 5-year-olds to play tackle football,” he says. “In my opinion, that’s unethical, and it needs to be addressed.”

WWE One of the Most Responsive Organizations

Nowinski says WWE has been one of the most responsive sports organizations for protecting athletes. A doctor is now ringside at every match as is an observer who knows the script, thereby allowing for instant medical intervention if something goes wrong. “Since everyone is trying to look like they have a concussion all the time, it takes a deep understanding of the business to recognize a real one,” he says.

But this hasn’t been the case with other sports. “I am eternally disappointed in the response of the professional sports industry to the knowledge of CTE and long-term concussion symptoms,” says Nowinski.

“For example, FIFA [international soccer’s governing body] still doesn’t allow doctors to evaluate [potentially concussed] players on the sidelines and put them back in the game with a free substitution [if they’re deemed okay]. Not giving players proper medical care for a brain injury is unethical,” he says. BU’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy diagnosed the first CTE case in soccer in 2012, and in 2015 Nowinski successfully lobbied US Soccer to ban heading the ball before age 11.

“Unfortunately, many governing bodies have circled the wagons in denying their sport causes CTE,” he continues. “FIFA, World Rugby, the NHL, even the NCAA and International Olympic Committee refuse to acknowledge it and, therefore, aren’t taking any steps to prevent it. They see it as a threat to their business model. Hopefully, now that the NIH and CDC are aligned about the risks of head impact in sports, this will begin to change.”

Meanwhile, research is continuing. Scientists are getting closer to being able to diagnose CTE in living humans, with ongoing studies using PET scans, blood markers, and spinal fluid markers. In 2019, researchers identified tau proteins specific to CTE that they believe are distinct from those of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. Next step would be developing a drug to slow the development of CTE once detected.

Nonetheless, athletes at all levels in impact sports still don’t fully appreciate the risks of repeated head trauma and especially sub-concussive blows. “I talk to former NFL and college players every week,” says Stern. “Some tell me, ‘I love the sport, it gave me so much, and I would do it again, but I’m not letting my grandchildren play.’ But others say, ‘As long as they know the risks, they can make their own decision.’ ”

Nowinski has a daughter who is 4 and a son who’s 2. Both play soccer but, thanks to dad, heading isn’t allowed in their age groups. If they continue playing sports, Nowinski says he’ll make sure they understand the risks and how to protect themselves. This is a conversation all parents should have with their kids at every level to make sure they play safe, he adds.

Those in the medical community can also volunteer their time to explain head trauma to athletes, coaches, and school administrators to be sure they understand its seriousness and are doing everything to protect players.

As you watch this year’s Super Bowl, Nowinski and his team would like you to keep something in mind. Those young men on the field for your entertainment are receiving mild brain trauma repeatedly throughout the game.

Even if it’s not a huge hit that gets replayed and makes everyone gasp, even if no one gets ushered into the little sideline tent for a concussion screening, even if no one loses consciousness, brain damage is still occurring. Watch the heads of the players during every play and think about what’s going on inside their skulls regardless of how big and strong those helmets look.

For more Medscape Neurology news, join us on Facebook and Twitter

Source: Read Full Article