A team of international scientists led by the Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) has discovered that Neisseria—a genus of bacteria that lives in the human body—is not as harmless as previously thought, and can cause infections in patients with bronchiectasis, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

In a study published today in Cell Host & Microbe, the team showed conclusive evidence that Neisseria species can cause disease in the lung and are linked to worsening bronchiectasis (a type of lung disease) in patients.

Bronchiectasis is a long-term condition where the airways of the lungs become abnormally enlarged for unknown reasons in up to 50% of Singaporean patients. The disease is up to four times more prevalent among Asians as compared to their Western counterparts and can also occur following recovery from tuberculosis. In Singapore, research at Tan Tock Seng Hospital described 420 incident-hospitalized bronchiectasis patients in 2017. The incidence rate is 10.6 per 100,000 and increases strongly with age.

Despite its prevalence among older people, no obvious cause is found in most cases of bronchiectasis and the condition tends to arise spontaneously and without warning.

To unravel the puzzle of why bronchiectasis worsens at a significantly greater rate among older Asian patients, the international team—spanning researchers and hospitals in Singapore, Malaysia, China, Australia, and the UK—led by LKCMedicine Associate Professor Sanjay Chotirmall, Provost’s Chair in Molecular Medicine, matched disease and infection data from 225 patients with bronchiectasis of Asian (Singapore and Malaysia) origin to those from bronchiectasis patients in Europe.

Neisseria: Not so harmless after all

While Neisseria species are well known to cause meningitis and gonorrhea, they are not known to infect lungs. Through detailed identification and meticulous characterization, the research team found that Neisseria dominated the microbiome of Asian patients with worsening bronchiectasis.

Specifically, bronchiectasis patients with predominant amounts of a subgroup of Neisseria called Neisseria subflava (N. subflava), experienced more severe disease and repeated infections (exacerbations) when compared to patients with bronchiectasis without such high amounts of Neisseria.

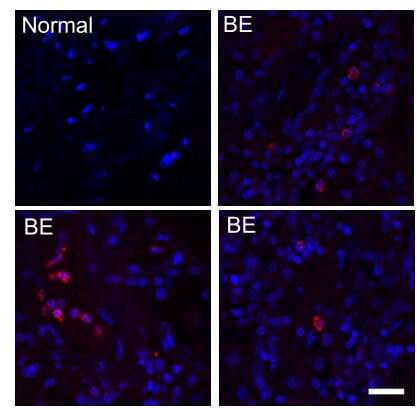

Upon further investigation using experimental cell and animal models, the research team confirmed that N. subflava causes cell disruption, resulting in inflammation and immune dysfunction in bronchiectasis patients with this bacterium.

Prior to this discovery, Neisseria was not considered to be a cause of lung infection or severe disease in bronchiectasis patients.

Lead investigator Prof. Chotirmall from LKCMedicine said, “Our findings have established, for the first time, that poorer clinical outcomes such as greater disease severity, poorer lung function and high repeated infection rates among bronchiectasis patients are closely associated to the bacteria Neisseria and that this finding is especially important for Asian patients.”

“This discovery is significant because it can change how we treat our bronchiectasis patients with this bacterium. Doctors will now need to think about Neisseria as a potential ‘culprit’ in patients who are worsening despite treatment, and to conduct tests to identify those who may be harboring this type of bacteria in their lungs. We hope that early identification will lead to personalized therapy, and consequently, better disease outcomes for Asian patients with this devastating disease,” said Prof. Chotirmall, who is also Assistant Dean (Faculty Affairs) at LKCMedicine.

This study reflects NTU’s efforts under NTU2025, the university’s five-year strategic plan that addresses humanity’s grand challenges such as human health. Conducted by international researchers from across various disciplines, the study also highlights NTU’s strength and focus on interdisciplinary research.

Broader relevance of Neisseria

Aside from linking Neisseria and severe bronchiectasis, the NTU-led research team also detected the presence of the same bacteria in other more common chronic respiratory conditions such as severe asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)—a condition that causes airflow blockage and breathing-related problems.

Using next-generation sequencing technologies, the team also sought to investigate where this bacterium may come from and sampled the homes of bronchiectasis patients with high amounts of Neisseria in their lungs. The researchers found the presence of the bacteria in the home environment, suggesting that the indoor living space and potentially the tropical climate may favor the presence of this bacteria in the Asian setting.

What is Neisseria?

The Neisseria bacteria species have been commonly identified as the cause of sexually transmitted infection like gonorrhea but also critically meningitis—an inflammation of the fluid and membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Its sub-species N. subflava, however, is known to be found in the oral mucosa, throat, and upper airway of humans previously without any known link to lung infections.

This family of bacteria has always been thought of as harmless to humans, and infections caused by them have not been described until now.

Co-author Professor Wang De Yun from the Department of Otolaryngology at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, said, “It is encouraging to see that we have made headway in identifying the Neisseria bacteria species as the cause of worsening bronchiectasis, the unlikely culprit that was originally not considered to be a threat. This comes as a strong reminder that we should not be too complacent when it comes to doing research and exercise more proactiveness in exploring various possibilities, as every seemingly innocent element could be a source of threat to our bodies and overall health.”

Co-author Andrew Tan, Associate Professor of Metabolic Disorders from LKCMedicine, said, “The reverse translational approach adopted in this work was crucial to our success. Starting from the ‘bedside’ where we studied real‐life patient experiences, we then worked backwards to uncover the biological process of the bacteria. Thanks to the interdisciplinary nature of the study, the team was able to interact with members from different research disciplines, offering an enjoyable experience while gaining unique insights into the disease.”

Source: Read Full Article