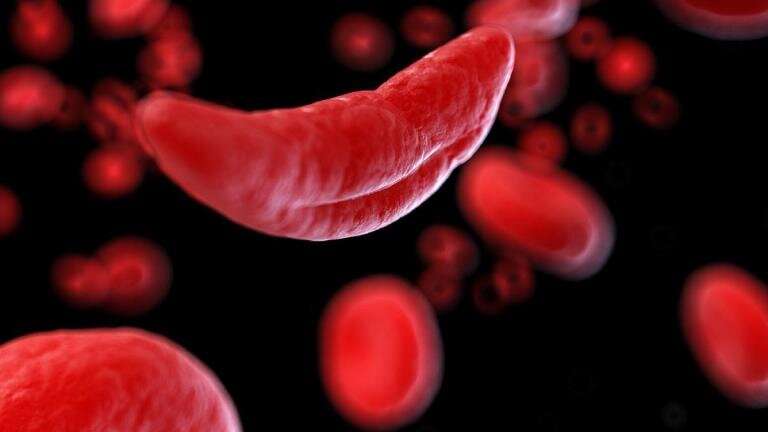

Sickle cell disease (SCD), a blood disorder that primarily affects people of African ancestry, can cause a variety of symptoms in patients, including stroke and cognitive impairment.

Hyacinth I. Hyacinth, Ph.D., MBBS, studies racial health disparities in neurological conditions at the University of Cincinnati and is currently leading two research projects to learn more about the relationship between sickle cell disease, stroke and cognitive impairment.

SCD and cognitive impairment

Patients with sickle cell disease tend to have high levels of inflammation in their body, including in the brain. Hyacinth said his previous research demonstrated that cognitive impairment is strongly correlated to the presence of inflammation specifically in the brain.

Hyacinth’s research found a drug called minocycline that blocks the inflammation was able to halt or reverse cognitive impairment in early studies of SCD animal models. Hyacinth is continuing to study how minocycline and other targeted drugs can treat cognitive impairment in sickle cell disease.

Minocycline is an antibiotic that blocks the conversion of molecules that are needed to activate inflammatory proteins. The drug also crosses the blood-brain barrier well and is thought to help neurons in the brain connect and mature.

While promising, Hyacinth said minocycline also tends to have some side effects in children, leading to the team also studying the effectiveness of other similar drugs that prevent inflammation and/or help form stronger neuron connections in the brain. The other drugs included in the study have more specific targets than minocycline, with the hope that this would lead to fewer side effects.

As the research in the lab continues, Hyacinth said he is working with members of his team (including Kristine Karkoska, MD, assistant professor in the UC College of Medicine’s Department of Internal Medicine) to design a first in sickle cell patients pilot clinical trial to test minocycline in adult patients with SCD and cognitive impairment.

SCD and stroke

According to Hyacinth, children with sickle cell disease are 300 times more likely to have a stroke compared to peers from the same ethnic group without sickle cell, and adults with SCD are 75 times more likely to have a stroke compared to age and race matched counterparts without SCD.

“So the question always is the same: How do we get from sickle cell to stroke? A lot of things happen in the middle,” said Hyacinth, associate professor of neurology and rehabilitation medicine and the Whitaker and Price Chair in Brain Health in UC’s College of Medicine.

Hyacinth’s research also aims to learn more about how blood vessels in the brain are affected by SCD and change over time. Using animal models, the research will aim to determine whether the changes in brain blood vessels due to SCD help lead to the development of stroke.

Patients with SCD have high white blood cell counts that Hyacinth said can be “particularly sticky” to blood vessels in the brain, which can potentially lead to a stroke.

Hyacinth and his team are studying if removing certain proteins that help the white blood cells stick to the blood vessels could prevent this process and in turn reduce the possibility of stroke.

“If we know that we can reduce the stickiness by taking out these proteins, then we can develop drug targets that target these proteins so that the white cells aren’t as sticky,” Hyacinth said. “And maybe that could help us prevent the development of stroke down the line.”

Personal motivation

Research into sickle cell disease is personal, Hyacinth said, as his nephew has SCD and he and his son both have sickle cell trait. People with sickle cell trait inherit one sickle cell gene from a parent and typically do not have symptoms of SCD, but they can pass the trait on to their children.

Hyacinth said he sees his research around SCD and other racial health disparities as a way to help right wrongs in society, whether brought about by human actions or by nature.

Source: Read Full Article