The traditional rice-based diet of some east-Asian population has brought a number of genomic adaptations that may contribute to mitigating the spread of diabetes and obesity. An international study led by the University of Bologna and published in the journal Evolutionary Applications has recently suggested this interesting hypothesis. Researchers analyzed and compared the genomes of more than 2,000 subjects from 124 south-east-Asian populations.

“We suggest that it may be possible that some east-Asian populations, whose ancestors started eating rice on a daily basis at least 10,000 years ago, have evolved genomic adaptations that mitigate the harmful effects of high-glycaemic diets on metabolism,” confirms Marco Sazzini, study coordinator and professor at the Department of Biology, Geology and Environmental Sciences of the University of Bologna. “Furthermore, these adaptations plausibly continue to play a pivotal role in protecting them from the negative effects that derive from major dietary alterations brought about by the globalization and westernization of their lifestyles. These alterations dramatically increased their consumption of food rich in processed sugar and with a high glycaemic index.”

Rice And Glycemic Index

Among the so-called domesticated cereals, rice presents a high glycaemic index and is rich in carbohydrates. This means that once ingested and digested, it causes sugar in the blood to increase. If eaten regularly and in large quantities, rice may represent a potential risk factor for developing insulin resistance and related metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes.

However, if we compare east-Asian people having used rice as a staple food for over 10,000 years with those in the Indian sub-continent, we soon find out that the latter show higher rates of diabetes and obesity than east-Asians. Why are these two groups different?

A 10,000-Year-Old Diet

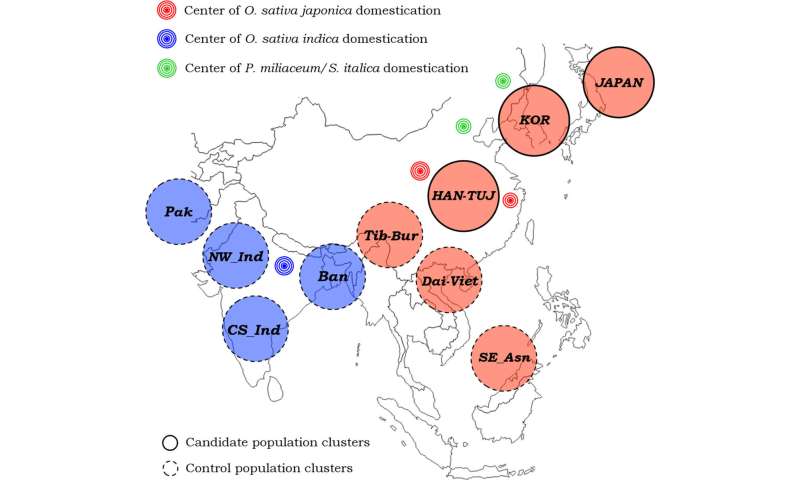

Archaeology may provide a hint to answering that question. Archaeobotanical findings in some eastern regions of Asia show that wild rice had been part of the inhabitants’ diets in the past starting 12,000 years ago. After rice domestication and the introduction of rice farming techniques, between 7,000 and 6,000 years ago, rice spread rapidly across Korea and Japan. In northern regions of the Indian sub-continent, an independent domestication process had started 4,000 years ago and brought to the selection of rice varieties presenting a lower glycaemic index if compared to east-Asian rice.

“Different rice varieties and a head start of millennia may have put populations in China, Korea, and Japan under a more pressing metabolic stress than that experienced by south Asian populations,” explains Arianna Landini, first author of this study and a Ph.D. student at the University of Edinburgh. “This might have allowed them to evolve genomic adaptations that mitigate the risk of becoming ill with metabolic diseases linked with a high-sugar diet.”

Rice And Genomic Adaptations

To test such a hypothesis, researchers analyzed the genome of more than 2,000 subjects from 124 east-Asian and south-Asian populations. Then, they compared the adaptive evolution observed in Chinese Han and Tujia ethnic groups, as well as in people of Korean and Japanese ancestry (with a long-standing tradition of rice-based diets) with that of people from regions of Pakistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Vietnam, and south-east Asia. Southeast Asian subjects were used as control groups because their adoption of cereal-based diets occurred many thousand years later.

“The genomic adaptations observed in control groups differ greatly from those of east Asian populations and are not related to metabolic stress due to a specific diet,” says Claudia Ojeda-Granados, one of the authors and a research fellow at the University of Bologna. “Chinese Han and Tujia ethnic groups, as well as people of Korean and Japanese ancestry show instead similar metabolic genomic adaptations.”

Some of the genetic modifications the researchers identified are associated with a lower BMI and a weaker risk of cardiovascular diseases thanks to a reduced conversion of carbohydrates into cholesterol and fatty acids. Some other adaptations favor a reduced insulin resistance as they negatively modulate the glucogenesis in the liver. Finally, some others stimulate the production of retinoic acid, which is a metabolite of vitamin A. Deficiency in this nutritional organic compound often causes health-issues in people eating a rice-based diet.

Source: Read Full Article