The exchange of gases between the air we breathe and our blood takes place via alveoli—tiny air sacs in our lungs. For this process to run smoothly, the epithelial cells of the alveoli produce a substance called “surfactant” that covers the alveoli like a film. This complex consists mainly of phospholipids and proteins and serves to reduce the surface tension of the alveoli. It also acts like a filter, reliably trapping bacteria and viruses that enter the lungs when we inhale.

Surfactant is continuously secreted, as the substance used is constantly being broken down and cleared away by alveolar macrophages (AMs)—scavenger cells on the alveoli. This process maintains the right balance between surfactant synthesis and disposal, a state known as homeostasis.

“But if it goes awry, more and more of the secretion accumulates in the lungs, which impairs breathing and increases the risk of lung infections,” explains Professor Alexander Mildner, a former Heisenberg fellow at the Max Delbrück Center and now a group leader at the University of Turku. Mildner is the last author of the study and has been researching macrophages for 20 years. “We wanted to know what prevents these pulmonary phagocytes from functioning properly,” he says. An overaccumulation of surfactant can result in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP)—a hitherto incurable disease that, in severe cases, requires patients’ lungs to be regularly flushed.

The crucial role of C/EBPb

The study was triggered by the discovery that alveolar macrophages cannot develop properly if they lack C/EBPb. Professor Achim Leutz has been researching the function of this transcription factor for many years. He is head of the Cell Differentiation and Tumorigenesis Lab at the MDC, which hosted Mildner’s independent research group. Other MDC researchers involved in the study included Dr. Uta Höpken and Dr. Darío Jesús Lupiáñez García. Through molecular biological studies and animal experiments, the team was able to explain the role of C/EBPb. Their results have now been published in the journal Science Immunology.

“We isolated alveolar macrophages from healthy mice and from those lacking the gene for C/EBPb and conducted in vitro tests on these immune cells,” explains the study’s lead author, Dr. Dorothea Dörr. “We also conducted various genome and transcriptome analyses of freshly isolated cells.”

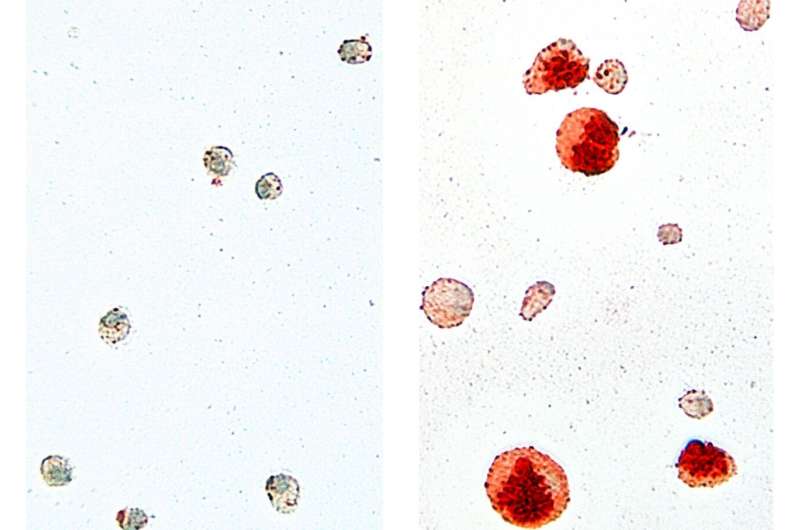

Specifically, the researcher investigated the biological and molecular properties of AMs—i.e., how well they are able to absorb and metabolize lipids. While the macrophages of healthy mice performed their tasks properly, those extracted from the genetically modified mice took up and stored a lot of the lipids but were unable to digest them. Instead, they swelled up into so-called “foam cells” and soon perished, redepositing the ingested lipids. The same phenomenon has been observed by doctors treating the lung disease PAP. In addition, the defective macrophages proved barely able to proliferate.

An important piece of the puzzle

Molecular analyses further showed that another important gene—also a transcription factor—is downregulated in mice lacking the C/EBPb gene: PPARg. When activated, this stimulates, among other things, the uptake of fatty acids and the differentiation of fat cells and macrophages in the body.

The lung disease PAP is generally the result of problems in the signaling pathway of the cytokine GM-CSF, which stands for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. “We already knew that certain essential functions of alveolar macrophages are controlled via the GM-CSF signaling pathway,” says Mildner. “Now we have found that macrophages deficient in C/EBPb show severe malfunctions in the proliferation of these cells and the degradation of surfactant, causing a PAP-like pathology in mice.”

It seems, therefore, that C/EBPb is the missing regulatory link between the GM-CSF and PPARg signaling pathways. “It’s like a jigsaw puzzle,” explains Leutz. “If you put in a certain piece, other missing pieces are suddenly much easier to find.”

A key to understanding other diseases?

Macrophages may be the scavenger cells of the immune system, but they do far more than just clear bacteria and viruses out of our system. Every organ has its own specialized macrophages. In the remodeling of the brain, for example, they have the task of breaking down neurons and synapses that are no longer needed. If they do not perform this task correctly, central nervous system diseases can develop.

Faulty lipid metabolism is not only the root cause of PAP; it is also responsible for atherosclerosis—a serious vascular disease. During this disease, more and more fat deposits accumulate on the artery walls, where they are trapped by white blood cells like macrophages. These macrophages ingest the lipids but cannot break them down properly, so they swell and form plaques. If the plaques ever break open, the fat inside escapes and may form artery-blocking clots—which can cause a stroke or heart attack.

“We think that the signaling pathway we have shed light on could be important in many lipid-related diseases,” says Mildner. “So the question now is whether what we’ve learned from alveolar macrophages might also help us better understand atherosclerosis and morbid obesity (adiposity).”

Source: Read Full Article