Mount Sinai scientists have discovered a neural mechanism that is believed to support advanced cognitive abilities such as planning and problem-solving. It does so by distributing information from single neurons to larger populations of neurons in the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain that temporarily stores and manipulates information.

It is well established that humans can only hold a limited amount of information in mind at a time, and that they enlist different cognitive strategies, like organizing information into lists or groups, to overcome these constraints. The research team found that when the brain uses these strategies to organize information, neural codes in the prefrontal cortex become less dependent on the highly selective responses of single neurons. Instead, they become distributed among a larger pool of neurons, which may make the information more reliable or robust. The findings were published online in Neuron on December 20.

“Our study gives the field an important new perspective on how the brain allocates its resources to improve cognitive performance,” says senior author Erin Rich, MD, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Neuroscience at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “Findings from our study will help scientists to better understand, and in the future to potentially treat, disorders of memory and cognition.”

The study was led by Feng-Kuei Chiang, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Rich’s lab who has previously studied functions of the prefrontal cortex in sequencing tasks.

Traditionally, studies of neural coding—which transforms electrical impulses from the neurons into memories, knowledge, decisions, and actions—have focused on selective responses of single neurons. The Mount Sinai team demonstrated the shortcomings of such an approach by designing a task to probe changes in the prefrontal cortex that result in improved cognitive performance. The task allowed the subjects to use a mnemonic (or memory aid) strategy to order information into a sequence.

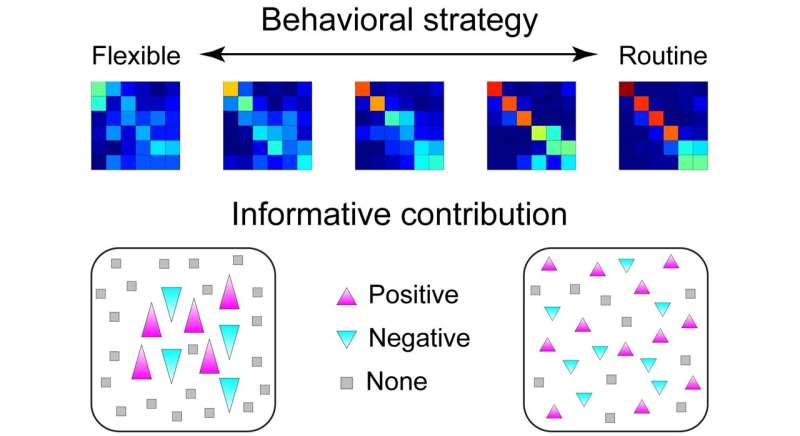

“We found that subjects spontaneously generated different selection patterns, including routine sequences, to decrease the working memory demands of the task,” said Dr. Chiang.

Researchers were surprised to find that interpretable responses of single neurons were a poor predictor of memory performance when subjects used the sequencing strategy to organize information held in the mind. Using the strategy reduced error rates in the task, but the activity of single neurons appeared to convey less information. They were able to reconcile these findings by showing that the information was not lost, but more widely distributed among a larger population of neurons. The task-relevant information could be recovered as well or better than when the codes were dominated by a smaller number of highly tuned neurons, and the distributed codes appeared to be more reliable, since they improved behavioral performance.

Source: Read Full Article