“Contagion,” a 2011 film about an influenza pandemic, ends with the first doses of a vaccine being allocated by lottery. COVID-19 vaccines are now being rolled out, including by lottery in some parts of the US. Governments around the world are having to write their own script for what might be regarded as the sequel to this film, covering the period from initial vaccine delivery to its use in the global fight against COVID-19.

Some wealthy countries, such as the UK and the US, have vaccinated a large part of the population. These countries have been able to secure contracts for the preferential supply of several vaccines, and have contracts or options in place for enough doses to vaccinate everyone several times over.

For the rest of the world, vaccine access is much less certain. While G20 leaders have pledged to ensure the fair distribution of coronavirus vaccines worldwide, substantial challenges remain. Covax, an initiative that aims to ensure that all countries will have equal access to COVID-19 vaccines, has a funding gap of US$4.3 billion (£3.1 billion) to buy the necessary vaccines. Some countries may need to wait until at least 2022 before even their most vulnerable are vaccinated.

The benefits of rapid global access to COVID-19 vaccines are clear. A modeling study suggested that a strategy in which the allocation of doses internationally is in proportion to countries’ population sizes is close to optimal in averting deaths. Importantly, it would also reduce the risk of the emergence and spread of new variants, some of which may be resistant to our current vaccines.

The rate of vaccine dissemination also influences the speed of economic recovery. It has been estimated that the economic cost of vaccine nationalism—where a few countries push to gain preferential access—could be up to US$1.2 trillion per year to the world’s economy.

In addition, there have been calls for developed countries to make available a proportion of their vaccine doses as a humanitarian buffer for groups such as asylum seekers. In the previous H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic there was a coordinated effort among developed countries to make a vaccine to protect the world’s poorest, including a pledge by President Obama to donate 10% of America’s vaccine supply—which was supported at the time by the public.

Overwhelming support for sharing the vaccine

A key factor that could shape the willingness of governments to make stockpiles of COVID-19 vaccines available to other countries is public opinion. That is, are the public in the countries that already have vaccines willing to give a proportion of their doses away?

While there is a long history of opinion polling on attitudes to foreign aid, there has been surprisingly little information on public attitudes to COVID-19 vaccine aid. To address this, we undertook an international survey that involved representative samples of 8,209 adults from Australia, Canada, France, Italy, Spain, the UK and the US. All these countries have pre-purchased one or more COVID-19 vaccines through either national agreements or multilateral arrangements such as the pre-purchasing by the European Union.

Adapting a question previously asked in the context of H1N1, we asked respondents if they supported their government donating some COVID-19 vaccine doses for distribution to poor countries that do not have the resources to buy their own vaccine. Those willing to donate indicated whether they favored an amount greater than, equal to, or less than 10% of the country’s stockpile.

Our results, which have recently been published in Nature Medicine, show a remarkable uniformity of opinion across countries with between 48% and 56% supporting some level of donation of vaccine stockpiles. Of those who supported vaccine donations, over 70% favored donating at least 10% of their country’s doses.

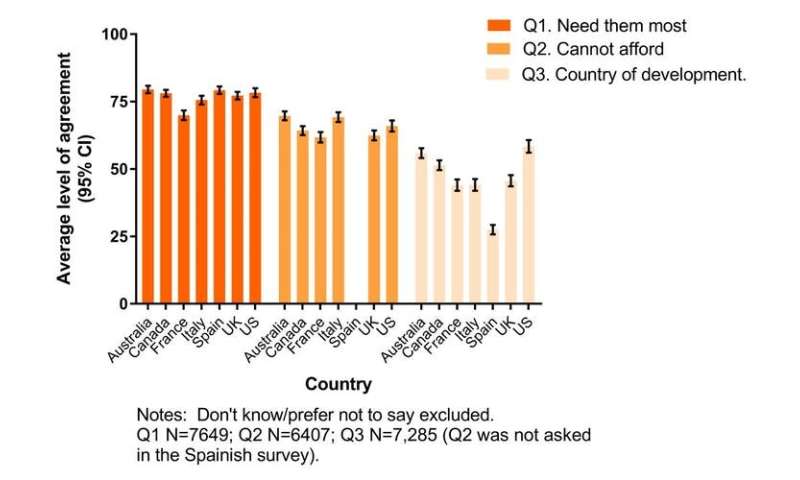

The graph below shows the average agreement for three different arguments for prioritizing global vaccine distribution (where zero means very much disagree, and 100 means very much agree).

How vaccines should be allocated, according to the public

The public favor allocation based on need, followed by inability to afford vaccination. There is less support for prioritizing allocation to those in the countries that developed the vaccines. So it would appear that governments do have majority support to start enacting their pledges to distribute COVID-19 vaccines around the world.

As many politicians know, public support can be ephemeral and so they need to communicate the major benefits an effective global vaccination program would bring—not only to recipients, but also to donors. More broadly, understanding and potentially influencing public opinion will be important components of any long-term strategies to combat COVID-19 and prevent future pandemics.

Preparing for the future

Beyond COVID-19, public support will be vital to put in place sustainable national and international public health institutions that can help prevent future pandemics.

Most of the current international institutions, such as the World Health Organization, were created in the immediate aftermath of the second world war. A successful coordinated international effort to tackle COVID-19 may provide a basis for updating and reforming these institutions to make them suitable for the 21st century.

Source: Read Full Article