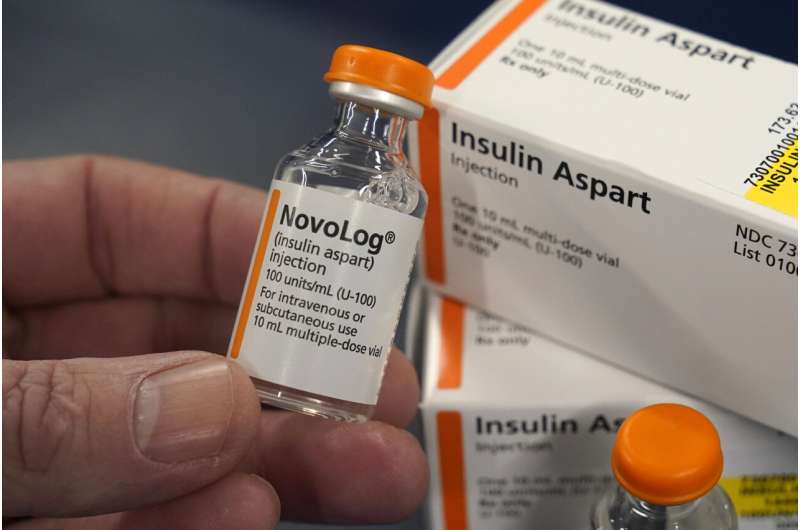

A vial of insulin cost $25 in 1995, back when Chris Noble was 5 years old and just learning how to manage his Type 1 diabetes with the help of his parents and his doctors.

Nearly three decades later, Noble says that same vial of insulin costs more than $300—a 12-fold increase for something he and millions like him can’t live without.

“It’s as essential as water,” Noble said.

Health care advocates have bemoaned for years that insulin, while inexpensive to produce, is held hostage by a U.S. health care system stubbornly resistant to reforms as companies monopolize and maximize profits.

Now, with several insulin patents nearing their expiration dates, California is looking to disrupt that market by making its own insulin and selling it for a much cheaper price. Last month, after a few years of study, state lawmakers approved $100 million for the project, with $50 million dedicated to developing three types of insulin and the rest set aside to invest in a manufacturing facility.

Gov. Gavin Newsom and state lawmakers still have many details to work out, including contracting with a private company to do most of the work. But the budget was a put-his-money-where-his-mouth-is moment for Newsom, who has been calling for the state to launch its own brand of generic drugs to lower the overall price of medication.

“Nothing epitomizes market failures more than the cost of insulin,” Newsom said in a video posted to his Twitter account. “California is now taking matters into our own hands.”

This wouldn’t be the first time California has made its own medicine. In 1990, about half of all cases of infant botulism—a rare illness that affects the large intestine—were in California. The California Department of Public Health got a federal grant to develop and test a treatment. The treatment won federal approval in 2003, and California has been making it ever since.

But the market for infant botulism treatments is small, with about 110 cases reported each year, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One course of California’s botulism treatment costs more than $57,000, according to a legislative analysis.

Meanwhile, about 7 million people in the United States require insulin to manage their diabetes. The human body converts most of the food we eat into sugar. The pancreas then produces insulin, which converts that sugar into energy. People who have diabetes don’t produce enough insulin. People with Type 1 diabetes must take insulin every day to survive.

Insulin was first discovered in 1920s by a team of Canadian scientists. They sold the patent to the University of Toronto for just $1, hoping the school would license the product to multiple companies to prevent a monopoly that would lead to high prices.

But over time, the insulin market was slowly cornered. Today, just three companies produce most of the world’s insulin. In the United States, the line between an insulin manufacturer and a patient is not straight. It zigs and zags between insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers—third parties that managed prescription drug benefits for health plans.

It’s that system that has kept the cost of insulin much higher in the United States than other countries, as more companies benefit from the higher price tag, said Kasia Lipska, an associate professor at the Yale School of Medicine.

“It creates this really weird incentive,” Lipska said.

California will try to break that incentive. The reason more companies haven’t entered the insulin market is because if they did, the established manufacturers would just undercut them, making it impossible to recoup their investment, said Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access California, a consumer advocacy group.

But California is in a different position because aside from selling insulin, it also buys the product every year for the millions of people on its publicly funded health plans. That means if California’s product drives down the price of insulin across the market, the state would still benefit.

“That’s why California’s market power matters,” Wright said. “To a Wall Street investor, driving down the cost of insulin means you might not be able to get your investment back. To California, driving down the price of insulin is a real savings to both taxpayers as well as to our residents.”

Still, there’s no guarantee California’s plan will work. For one thing, insurers and pharmacy benefit managers might not cover California’s insulin products, making it more difficult for patients to get them.

Sarah Sutton, director of public affairs for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, said a better idea would be for California to focus on “commonsense solutions” to address the role pharmacy benefit managers play in insulin pricing.

“That would bring real relief to patients right now,” she said.

Dr. Mark Ghaly, secretary of the California Health and Human Services Agency, said he hopes a state as large as California making its own insulin would significantly diminish the role of pharmacy benefit managers in insulin pricing.

If successful, Ghaly said he thinks the price of California-branded insulin would be so competitive that patients could buy it off the shelf cheaper than going through their insurance plan.

Source: Read Full Article