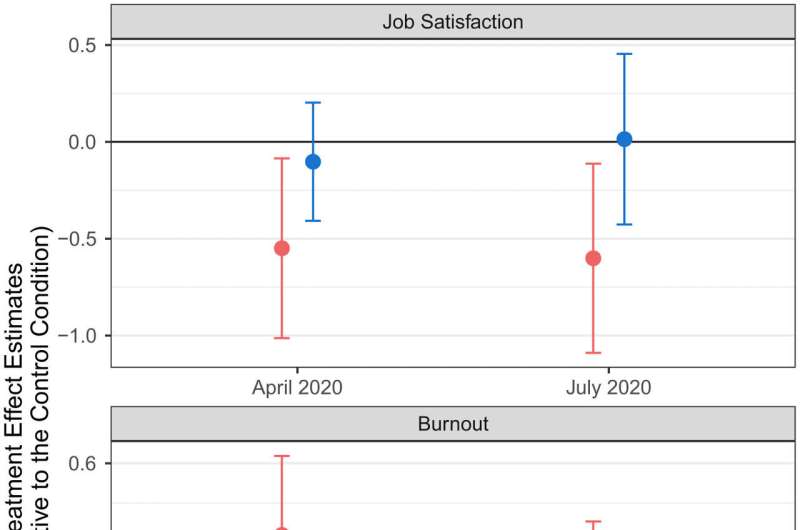

A commonly used behavioral intervention—informing primary care physicians about how their performance compares to that of their peers—has no statistically significant impact on preventive care performance. It does, however, decrease physicians’ job satisfaction while increasing burnout.

Burnout rates among physicians are rising—often resulting in mental health problems, job turnover, and higher healthcare costs. Meanwhile, health system leaders and policymakers are concerned with motivating physicians to adhere to medical best practices. One commonly used strategy is showing physicians how their job performance compares to that of their peers. It is critical to assess how such peer comparison information influences physicians’ well-being at work, beyond their job performance.

The UCLA Department of Medicine’s Quality Team and researchers from the UCLA Anderson School of Management conducted a five-month field experiment involving 199 primary care physicians and 46,631 patients to examine the impact of a peer comparison intervention on physicians’ job performance, job satisfaction, and burnout. Their results were published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The evidence suggests that the peer comparison intervention inadvertently signaled a lack of support from leadership, thus reducing physicians’ job satisfaction while increasing burnout. The study also shows that training leaders on how to best support physicians and contextualize the peer comparison intervention mitigated such negative effects on perceptions about leadership support and physician well-being.

“Behavioral interventions such as providing peer comparison information offer attractive, cost-effective ways to promote positive behavior change,” said Dr. Justin Zhang, resident physician in internal medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, who co-led the study while a UCLA medical student.

“This research highlights the importance of assessing less visible outcomes, such as job satisfaction and burnout, when policymakers and organizational leaders implement seemingly innocuous behavioral interventions. This work also underscores the importance of attending to the way in which an intervention may inadvertently change employees’ perceptions of their managers and thus elicit negative reactions.

“To preempt negative perceptions, such as reduced feelings of leadership support, this research suggests that organizational leaders ought to engage employees in the design phase of an intervention, probe their feelings, and revise the design if needed.

Source: Read Full Article