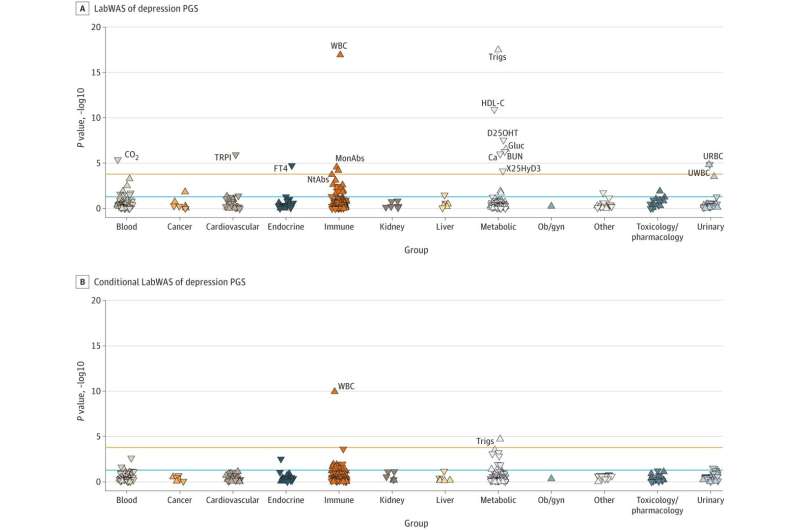

Researchers across four health care systems, including Vanderbilt University Medical Center, have found that increased depression polygenic scores are associated with increased white blood cell count, highlighting the importance of the immune system in the etiology of depression.

Despite a wide understanding of depression as a psychiatric disorder, depression’s underlying biological effects are still poorly understood, says Lea Davis, Ph.D., associate professor of Biomedical Informatics, assistant professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and an author of the JAMA Psychiatry paper.

“We know that there’s a strong relationship between depression and several chronic health conditions, and we also know there’s a relationship between depression and inflammation,” Davis said.

“What we don’t know is exactly how they’re connected, which condition causes the other or if there’s something underlying that causes both.”

To answer that question, Davis and the research team, which consisted of researchers from VUMC, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Mass General Brigham (a hospital and physicians network that includes Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital) and the Million Veteran Program, studied two groups—people who had depression and people who did not, but were at a high genetic risk for developing depression.

The team found a strong connection between depression polygenic scores and white blood cell count.

They also found that even having a high genetic risk for depression was enough to contribute to an elevated level of white blood cells. Primary analyses for the study were conducted in VUMC’s biobank, with replication analyses conducted across the three other health care systems. Results from 382,452 patients’ electronic health record data were meta-analyzed across all four systems.

Cross-institutional collaboration is a necessity when it comes to understanding things like depression, Davis says.

“It’s been so powerful to have a whole network of institutions with biobanks all working together. The problems that we’re trying to tackle are so complex that being able to bring massive amounts of data together to untangle complicated biological problems is essential,” she said.

The researchers’ results show a feedback loop in which people who are at a higher genetic risk for depression also have a higher baseline level of inflammation. If a person develops depression, that further increases the biomarkers related to inflammation.

“The relationship between depression polygenic scores and white blood cell count was statistically strong,” said Davis. “People with higher polygenic scores for depression had a higher white blood cell count, but the number was still considered in the ‘normal’ range. This suggests that sustained, but not abnormal, activation of the immune system may be contributing to depression.”

Their findings also suggest that the association between depression polygenic scores and increased white blood cell count are bidirectional.

Davis and Julia Sealock, a graduate student in Human Genetics and first author on the paper, hope the results motivate future development of clinical biomarkers and targeted treatment options for depression.

“I think our research contributes to mounting evidence of a pro-inflammatory state in depression and creates an exciting opportunity to think about a new class of anti-depressive therapies focused on lowering pro-inflammatory markers,” Sealock said. “We can now start asking if lowering pro-inflammatory markers leads to an anti-depressive effect. If so, this could bring about a paradigm shift in depression treatment from focusing on changing chemistry in the brain to changing biomarkers in the periphery.”

“We hope this research helps solidify the idea that mental and physical health cannot be separated,” Sealock said.

Source: Read Full Article