At the end of the year, Nadia Nadim will join the tens of thousands of medical students who will exchange their short white coats for the long ones of practicing physicians. Unlike other future doctors, this soon-to-be reconstructive surgeon has also been wearing a uniform that’s more than white. She has donned brightly colored red, purple, or blue jerseys as a striker for teams in the US National Women’s Soccer League and the Danish National football team.

Nadim balances competition in high-level international soccer with obtaining her medical education.

The 33-year-old found her way into medicine after a harrowing childhood. Following the murder of her father by the Taliban, Nadia, her mother, and her four sisters fled Afghanistan in fear for their lives. They sought refuge in Denmark, where Nadia first discovered football [soccer] and a growing call to become a humanitarian activist. Just one semester away from becoming a doctor, and still sustaining a demanding professional football schedule, Medscape spoke with her about her remarkable story.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Medscape: Would you mind telling us a bit about your background and your journey into medicine?

Nadia: I was born in Afghanistan and was raised there until I was 10 years old. Then we had to flee the country because of war. We came to Denmark at the start of sixth grade. At that point, I didn’t really understand the language. I didn’t understand a lot of things. The only thing I kind of knew was math because my mom was teaching us at home.

My mom had always emphasized the importance of education. She said that it can get you out of any situation in your life. If you’re having problems or are in poverty or whatever, education is the key. She was the first kid in her family to get education. No one before her ever went to school, especially not girls.

My mom wanted to become a doctor, but then she got married and her plans changed. She always had this dream and then wanted one of her kids to become a doctor. When I heard that I was like ‘Hell no, I’m not gonna. I’m not gonna fulfill your dreams.’ My older sister wanted to become a doctor, and I was like, ‘I’m not gonna become a doctor. I’m gonna do something else. I’m gonna try to become rich.’

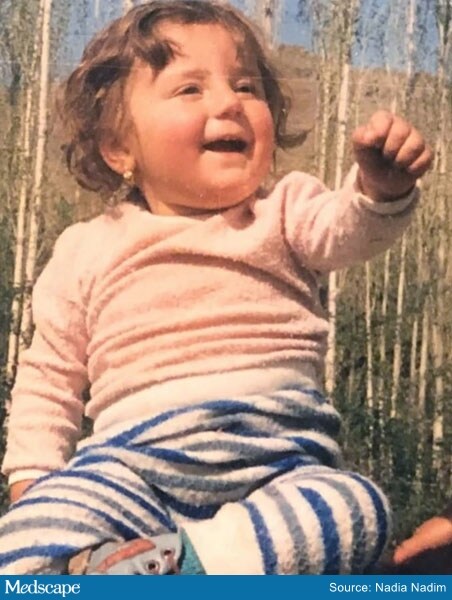

Nadim as a child in Afghanistan.

I remember in ninth grade, we had this one week where you get to choose what you want to do. I chose to go to the clinic close to our house, not because I had the biggest interest but because it was close and I could sleep in longer…

The week that I was there, I was really surprised. I thought ‘Wow, this is really cool to be in the hospital.’ I saw some cosmetic operations and eye surgeries. I could see myself in that environment. I love the fact the doctors are able to help people, especially the ones who are really in need. I thought ‘Maybe I should give this a go.’

So I signed up [for medical school]. I got in. I didn’t tell my mom. I told her that I applied to business school and was accepted. She’s was half-heartedly saying ‘Oh, I’m so proud of you!’ She didn’t really mean it.

I remember being in the first semester and thinking ‘I’ve chosen so right.’ I loved everything about med school, from the blood to the conversations that you have with your patients. I love it.

Obviously, football is a big part of your life as well. How have you balanced medical training with your work as an athlete on a global stage?

It hasn’t been easy. I did my bachelor’s degree as normal as everyone else because it was possible for me to be in school from 7 AM to 3 PM. My football training was at 6 PM. It was possible but also really tough.

We have these huge exams in Denmark where you are literally tested on 6, 7, or 8 big subjects. The failure rate is really high. I was selected for the Danish national team. The time for my exam was literally the same time that I was about to go to camp. I remember there was this lady… I explained my problem, and she said ‘Well, I’m sorry, this is it. You have to make a choice. No one can play football and be a doctor, so I guess you have to make a choice.’ I wanted to prove her wrong.

In addition to soccer and medicine, Nadim has also dedicated herself to humanitarian work.

What advice would you have for students who may be in such similar situations, in which they have a counselor or an advisor who isn’t very supportive?

I think there’s always two ways: Either you’re gonna listen and be like ‘OK, this is it. I give up.’ Or, if you’re really passionate about it, you’re gonna go the hard way, which is that you do your thing and then slowly everything is gonna go your way.

I think it’s just about being strong enough to “do you.” I think that’s important. Don’t just give up easily just because you’ve been told, ‘We’ve never done this before. It’s impossible.’ I don’t believe that [impossible] is something that exists. I think if you want to do something, there’s always a way. You just have to find it.

I have never taken no for an answer, I guess. But it’s not gonna be easy…

Given all that is on your plate, how do you avoid burnout?

I love doing active stuff. I have a lot of hobbies. I also enjoy just chilling. If my football allows it, and I’m fresh, I love to do stuff outside like tennis, basketball, and swimming.

I love to watch Bollywood movies, just because I speak Hindi. They have something a bit magical around them, like fairy tale movies. I love to watch Korean dramas. I think I’m always interested in other cultures.

You also have a lot of other projects in the works. Could you tell us briefly about some that you’re currently working on?

One of the things that is really close to my heart and I’m passionate about is volunteer work. You know, the humanitarian organizations that do so much in the world. I’ve been on the receiving hand on the other side. I know that a little tiny help can have a huge impact on your character and your future. That’s probably also one of the reasons I want to be a doctor.

One of the organizations that I work with is the Danish Refugee Council. I have visited refugee camps around the world. I’ve been in Jordan and Kenya, and also Denmark. I’m also ambassador for [United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization] UNESCO’s education for girls. Because, again, I think education is the key to a lot of the problems we do face right now.

For instance, let’s say racism, which is a huge thing. You could probably decrease that by educating people. Ignorance, I think, is a huge factor, the fear that you see among a lot of people because of Islam. It’s just people being ignorant. They don’t know. They just assume or they see a certain group and think that they are the representation for the entire population. All of this ends with education.

If you could educate people. I think a lot of problems would disappear or at least get better. So yeah, I am really busy. But whenever I have a bit of time, I try to use it on making a change.

I started by saying that my mom said education is very important. I think that’s something that my entire family has taken to. My oldest [sister] is a doctor, and then I have two nurses in the family, my youngest sisters. I think a goal is to have a clinic all together.

Khayla Daniel is a second-year MPH candidate at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health. She is interested in pursuing a career in healthcare administration.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. Here’s how to send Medscape a story tip.

Source: Read Full Article