Patients with heart failure often have shortness of breath and become fatigued quickly. They frequently suffer from water retention, heart palpitations, and dizziness. The condition can be triggered by a combination of elevated blood pressure, diabetes, and kidney disease, or by acute events such as heart attacks or infections. As people age, the number of adverse factors increase, so heart failure primarily affects older people, especially women.

Although the symptoms are similar, there are various causes. In one form of the condition, the pumping function of the heart is impaired. This can, however, be improved with widely available medication. In the other form, the heart pumps with adequate force, but the chambers of the heart—the ventricles—fail to fill properly because the ventricular walls become thickened or stiff. There is currently no effective therapy for this form of heart failure.

Together with colleagues from Heidelberg University and the California-based company Ionis Pharmaceuticals a team led by Professor Michael Gotthardt of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) has now developed a therapeutic agent to improve the treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. The scientists have described their new therapeutic approach in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

The giant protein titin influences heart elasticity

The mechanics of the heart depend on an elastic giant protein called titin. It is produced by heart muscle cells in distinct variants or isoforms that differ in their flexibility. While very elastic titin proteins predominate in infants, later, when growth and remodeling are completed, stiffer titin isoforms are produced to increase pumping efficiency. In heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, thickened heart walls, intercalated connective tissue, and stiffer titin filaments may lead to impaired filling of the ventricles.

Heart muscle cells are virtually unable to renew themselves in adults. Yet the constant pumping activity of the heart muscle puts such severe strain on titin that the worn-out proteins must be broken down and replaced every three to four days. “The mechanical properties of titin proteins are difficult to adjust,” says Gotthardt. “But we can now intervene in the process preceding protein synthesis—that is alternative splicing.” Alternative splicing is a clever trick that nature has devised to create a variety of similar proteins based on a single gene—including the different forms of titin. This process is controlled by splicing factors. “One of these, the master regulator RBM20, is a suitable target that we can address therapeutically,” explains Gotthardt.

Antisense agent deactivates RBM20

RBM20 determines the elastic, contractile, and electrical properties of the heart chambers. Its significance was shown in preliminary experiments with mice that, due to a deletion, can produce only half as much RBM20 as normal mice: In the deficient mice, there was a shift to more elastic titin isoforms. Together with the Ionis researchers, the scientists now began looking for a way to influence RBM20. “We were surprised at how easily this could be done,” says Gotthardt—namely with antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs). These are short chains of single-stranded nucleic acids that are synthetically produced. They bind specifically to the complementary RNA sequence, the blueprint of the targeted protein, thereby blocking its synthesis.

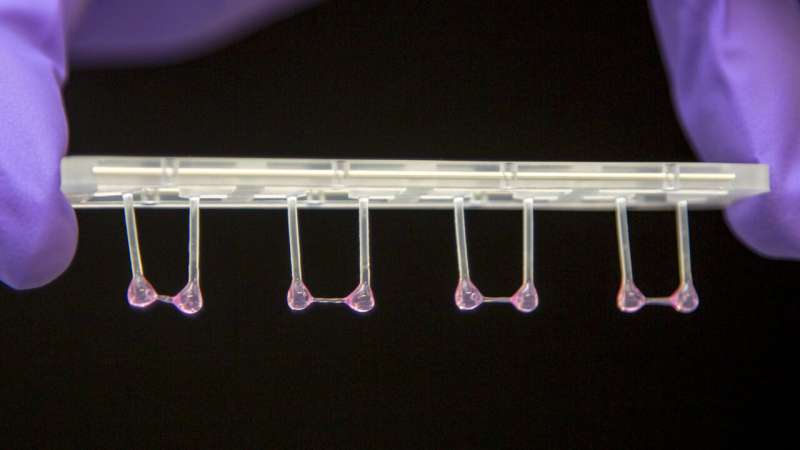

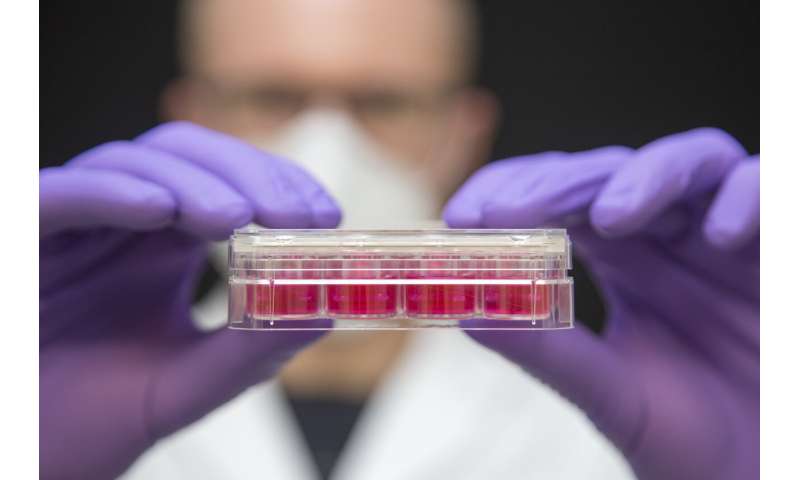

Dr. Michael Radke, a lead author of the study, first successfully tested the ASOs in mice with stiffer heart walls. His colleague Victor Badillo Lisakowski then grew heart muscle cells derived from human stem cells into artificial heart tissue. The tiny 3D structures can be stimulated to contract and relax when they encounter resistance, enabling them to mimic the pumping action of the heart. This artificial heart tissue also showed what effect the treatment had: The researchers were able to demonstrate that the ASO molecules actually penetrate the cells and trigger the desired response. “These tests on artificial heart tissue were an important step, because the primary sequences for titin are not identical in mice and humans,” says Radke.

A weekly injection?

For the first time, antisense oligonucleotides have been successfully used to therapeutically influence alternative splicing in cardiac disease. The Ionis researchers were able to stabilize the sensitive molecule in such a way that it reaches the striated muscles in the mouse model and is not already degraded in the blood, liver, or eliminated by the kidneys. Most of it winds up in the heart, with some entering the skeletal muscle. “In the mouse model, however, we observed that it has no disruptive effect if increased amounts of elastic titin are formed in skeletal muscle,” says Radke.

Source: Read Full Article