Pradeep Bansal considered the five capsules he was about to swallow. Together they made up a 25 milligram dose of a substance that, in another setting, could have landed him in federal prison.

The substance was psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms. To be more exact, it was a synthetic form of psilocybin called COMP360, made to pharmaceutical standards by a company called COMPASS Pathways. He was taking it as part of an FDA-approved clinical study on mental health therapy for people with cancer.

Dr Pradeep Bansal

Bansal, a New York gastroenterologist, was far more comfortable giving medical treatment than receiving it. But he was getting used to it.

He had already been through surgery and a number of other treatments to address the physical aspects of his cancer. The psilocybin was to address the mental aspects — the crushing anxiety and depression that had stuck with him after his diagnosis.

Bansal did not arrive at this moment lightly.

“I was extremely skeptical going into this process,” says Bansal, who during a long medical career had looked with distrust and even disdain at alternative therapies.

“I don’t have much patience for holistic medicine, homeopathy, acupuncture, or alternative medicines with claims of spiritual upliftment or altered states of mind.”

But Bansal had done his homework on psilocybin and was impressed.

People with late-stage cancer and other serious health conditions who got psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy had “significant decreases” in anxiety and depression as long as 12 months after the treatment, according to studies published in 2011, 2014, and 2016.

One study from Johns Hopkins University tracked the effects of a single guided dose of psilocybin in terminal cancer patients with anxiety and depression. More than 80% had a “significant decrease” in symptoms — even 6 months after treatment — with more than 60% of the group remaining in the normal mood range.

For the study Bansal joined, there had been weeks of screening and consultation and preparation in a strictly controlled scientific trial.

And yet even with all that he had learned, even with his psychiatrist-guide by his side, he was afraid. Afraid of what he might experience under the powerful effects of psilocybin. And afraid that this was all a misguided waste of time — that his mental angst would still be there when it was all over.

He knew that psilocybin, like other psychedelic substances, could take you on a “trip” — could remove you, at least for a time, from normal conscious experience.

Maybe he would feel “funny,” he thought. Maybe he would have some hallucinations. But how would that change the reality of his cancer? How would it lift the black dread and anxiety he felt about his future?

Stuck in a Dark Place

Bansal had first noticed blood in his urine — a lot of it — in September 2019.

Two months later, doctors diagnosed cancer in his right kidney. He would need surgery to remove the kidney and surrounding lymph nodes (an operation called radical nephrectomy).

It was a shock, says Bansal. But the diagnosis and the surgery happened so quickly that he hardly had time to think. And treatment results seemed good. The cancer was only in stage I and the CT scans showed no signs of cancer after surgery.

“We were so relieved. Everyone was so happy,” Bansal says. “They didn’t even give me chemotherapy after surgery because it seemed so early.”

But a routine scan in June 2020 revealed more cancer in his lung. Within a couple of months, it was in his bladder too.

“It was devastating,” Bansal says. “I went from thinking I was healthy again to stage IV cancer.”

As doctors scheduled surgery to remove part of his lung, Bansal started on painful immunotherapy (BCG therapy) for his bladder.

At this point, from a psychological standpoint, Bansal was reeling. As a doctor, he knew all too well the meaning of stage IV cancer.

With two adult children and a grandchild on the way, Bansal had been looking forward to retirement with his wife of almost 40 years. “Suddenly, I wasn’t sure I was going to last that long,” Bansal recalls.

“I was in a very dark place. I was very anxious, very depressed from lack of sleep.”

He saw a therapist about his cancer diagnosis and maintained his regular meditation practice at home. He hired a personal trainer and tried to focus on any good news that he got about his treatment.

Those things helped, but not enough.

The basic facts were inescapable. His cancer might end everything. He couldn’t stop thinking about it. And then he couldn’t stop thinking about how he couldn’t stop thinking about it.

If the worst happened, he didn’t want to spend his last days in a state of such relentless existential angst. And it wasn’t just for himself. He wanted to be strong and mentally present for his family and his loved ones and his patients.

As he searched for something to ease his mental anguish, Bansal recalled some psychedelic research on end-of-life anxiety and depression that he’d read about in Michael Pollan’s 2018 book on psychedelics, How to Change Your Mind.

The studies were small and the research was new, but Bansal was impressed enough with the results to take a chance. He called a lead researcher of one of the studies, a fellow New York doctor, and eventually found himself accepted into a new study.

Starting the Journey

By the time Bansal arrived at the Bill Richards Center for Healing at the Aquilino Cancer Center in Rockville, MD, he had already been through weeks of screening.

The main requirements for the study were a cancer diagnosis and a measurable level of depression. But study participants also had to be physically fit enough to handle the medication, and psychologically free from a personal or family history of psychosis or schizophrenia. (The study also required participants to slowly wean themselves from medications like SSRIs for depression or anti-anxiety medications under the strict supervision of a qualified doctor.)

Bansal’s week of treatment began almost immediately on arrival at Aquilino. Everything was carefully choreographed but not rushed. From Monday through Wednesday, doctors followed his physical health with exams, ECGs, and blood work. And most importantly, they began to prepare him for the “dosing session” on Thursday when he would take the psilocybin.

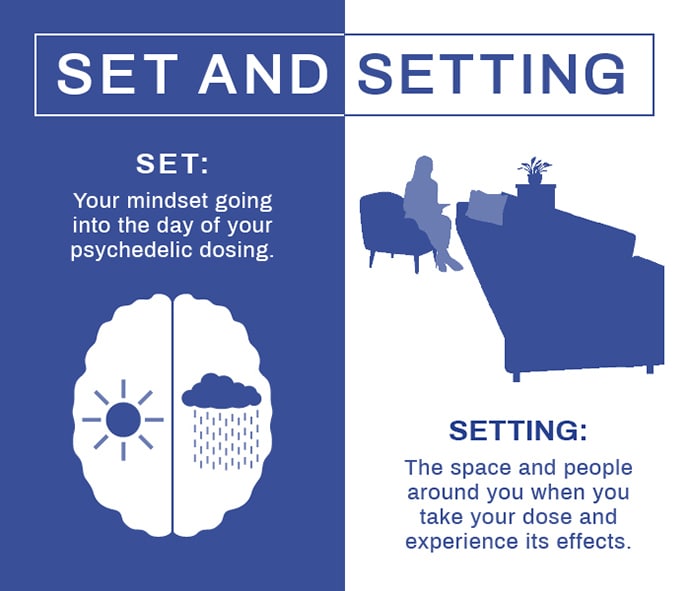

This is the careful crafting of “set and setting” stressed in so many psychedelic therapies. “Set” refers to your mindset going into the drug experience. “Setting” is the space and people around you when the drug sends you into an altered state of consciousness.

Bansal met several times with at least three therapists in the days leading up to his dosing. He attended 4-plus hours of therapist-led group sessions with other people who would get a dosing on the same day. Together, they talked about what to expect during the experience and what to do in the face of fear or panic.

He connected with a therapist who would be his personal guide. Bansal’s therapist was a military psychiatrist with over 30 years’ experience.

“He was there with me from day 1, and so we established a relationship,” Bansal says.

“He asked me a lot of personal background history — you know, my religious convictions, aspirations, all those things.”

“Trust and let go,” was a kind of mantra for the treatment repeated by his guide and other doctors.

For Bansal, a doctor and scientist accustomed to using hard facts rather than touchy-feely slogans to navigate the care of patients, it was an adjustment, to say the least.

But he did his best to set aside his doubts and embrace the journey he was about to take.

The Day of the Trip

Thursday morning finally arrived. The setting of the dosing room was warm and welcoming, more like a cozy home study than a hospital room.

This matters more than you might think. First, because it’s important that you feel safe, open, and comfortable enough to let go and enter into a therapeutic process. But also because though rare, it’s possible — especially with psilocybin — for people to lose track of where they are and what they’re doing and put themselves or others in danger.

The dose, 25 milligrams, had been carefully calibrated to induce a psychedelic experience sufficient for therapy. Much less than that, say 10 milligrams, isn’t enough for most people to enter this state. A double dose, 50 milligrams, though not physically unsafe, may leave you too incoherent to have the useful insights key to therapeutic value.

A doctor, the lead investigator of the study, brought the five capsules into the room in an intricately carved crucible with a small ceremonial cup that held the water with which to take it.

“It was very solemn,” Bansal says. “He sat down with me in a very calming way.”

The doctor said: “Don’t worry about it. Just trust and let go.”

And that’s just what he did.

Bansal swallowed the capsules and lay down. The doctor quietly left the room so that Bansal and his psychiatrist guide could begin their session together.

Special eye shades kept him in the pitch dark whether his eyes were open or closed. Headphones streamed a curated musical playlist – much of it Western classical like Strauss, Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven — but also modern electronica and other music from cultures around the globe.

Bansal would remain here, with his therapist-guide by his side, in largely this same position, for the next 7-and-a-half hours.

It took about 45 minutes for the medication to kick in.

The Investigator

The doctor who brought the capsules into the dosing room was Manish Agrawal, MD, co-director of clinical research at the Aquilino Cancer Center and lead investigator of the study.

Dr Manish Agrawal

Agrawal trained at the National Cancer Institute and practiced for many years as an oncologist before developing an interest in psychedelic therapies. It was his work with cancer patients that drew him to psychedelics in the first place.

He had seen too many of his patients mentally wrecked by a cancer diagnosis, and he often felt helpless to comfort them.

“You take care of the physical aspects of the cancer, right? You talk about side effects and recommend another scan to look for recurrence.”

“But what about the psychological effects?”

They can be very serious and too often go ignored, says Agrawal. Your plans for the future suddenly become moot. You may be concerned about your ability to work or worried about the pain and suffering and financial strain that might be ahead for both you and your family. And to top it all off, you’re staring into the face of your own mortality.

So it’s no wonder, says Agrawal, that many people develop clinical levels of anxiety and depression after a cancer diagnosis.

Like Bansal, Agrawal had been impressed by early studies on psilocybin-assisted therapies for end-of-life anxiety and depression. He had tried other approaches — support groups, one-on-one therapy, religious counselors, psychiatrist-prescribed medication — but he was never really happy with the results.

To Agrawal, psilocybin-assisted therapy was the first thing that looked like it could really make a difference.

And so after his psychedelic certification at the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS), Agrawal was determined to change his approach.

The result was The Bill Richards Center for Healing at Aquilino Cancer Center, built specifically to study psychedelic-assisted therapies for psychological distress in people with cancer. The mission of the center is to help develop safe, FDA-approved psychedelic therapies for the mental health of cancer patients, and, once approved, provide a state-of-the-art facility and staff to administer those treatments.

A Trip Into the Unknown

Back in the dosing room, Bansal was starting to feel the effects of the medication. As the psilocybin kicked in, spectacular images swirled.

“It was as if a million stained glass windows had suddenly come to life and were dancing in front of my vision,” Bansal says.

There were moving landscapes and intricate swirling patterns and massive stages in the sky where he saw orchestras playing the music he was hearing.

Bansal saw himself being crushed by a huge machine and buried, dead, in the Earth. He died and returned to life several times, glided over the top of New York City with the skyscrapers just below him, and took in the vision of the entire universe.

“I saw this expanse of the sky that was limitless. And there was this prehistoric reptile creature that spanned galaxies in the sky ahead of me who was dying. I said, ‘My God, the universe is dying,’ but then after a few moments, the universe came to life again in a burst of stars exploding.”

All the while, Bansal says, he was well aware that it was simply his mind creating these images, thoughts, and ideas. He knew he was in a safe room wearing eyeshades and headphones.

And yet, he says, it felt true. “The images and feelings are so powerful that you cannot help but believe they are in some way a part of reality.”

“At one point, I saw this giant Ferris wheel coming towards me and it was full of giant crabs, clicking and clacking their pincers. And my brain told me, ‘That’s my cancer!'”

Bansal was terrified. But he and his therapist had arranged a system of signals before the session. “If I was feeling afraid, I would hold his hand and if I had other issues, I would raise my hand. If I was feeling good, I would give him a thumbs up.”

Bansal reached out to his therapist and grasped his hand. “I said, ‘My cancer is coming at me!'”

His therapist was clear about what to do: Stand firm and walk toward it.

“That’s what they tell you: If you see anything frightening, you face it. And that’s the whole point of this exercise. And so, I stood and walked forward, and it just blew off in a puff of smoke.”

A State of Peace

Around 3 hours into the experience, Bansal started to feel an immense sense of peace, happiness, and even comfort.

“I felt like I was watching a movie or a multidimensional slideshow. I was also a part of the movie. I felt like I could tell my mind what I wanted to see, and it would show it to me. It’s almost like you can mold your own visions. It was mystical.”

After about 8 hours, as the effects of the drug wore off, Bansal removed his eyeshades and headphones. He was completely drained.

“Even though I was lying down on my back for 7 hours, I felt like I had been run over by a truck. I was exhausted beyond belief physically and mentally.”

This was partly due to the fact that he hadn’t eaten much during the session. But mostly, says Bansal, it was due to the searing emotional intensity of the experience.

After the Journey

It’s hard to put into words, says Bansal, what this treatment has done for his life. He feels as if he has stumbled onto something very precious that had been right in front of him all along. He wrote of his change in perspective almost obsessively in his journal in the days and weeks after treatment. One passage reads:

“It seems that as time is passing on, I’m becoming more relaxed and hopeful, more calm, and at peace. Family has become even more important to me now. Money, politics, material gains, alcohol, seem less important.”

And yet there was nothing “easy” about the experience. In fact, in some ways the experience demanded more from him.

“I feel I need to be more compassionate and considerate — less irritable and angry, more understanding of others’ needs. I feel I need to be a better human being, a better patient, a better father, and a better doctor for my patients.”

The experience, he says, gave him something far more important than mere ease. It gave him a sense of meaning.

From his journal:

“I died, and I was reborn. If I survived this, then I can face anything and anybody in the cosmic scheme. I can become part of it.

“How many sorrows in the universe? My cancer is nothing. Life does not end with the end of life. What was will be again. Eternally.”

That’s not an unusual response, according to the namesake of The Bill Richards Center for Healing. Richards, PhD, has worked in the world of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy since 1963.

A psychologist with decades of experience, Richards and his colleagues figure that, with few possible exceptions, he has helped treat more people with psychedelic therapies than anyone alive in Western medicine today. At Aquilino, he works directly with patients and oversees the therapy protocol that goes along with the psilocybin dosing sessions.

“It’s inspiring,” Richards says.

“You meet someone who’s very depressed and scared and isolating from family and having all kinds of physical complaints. And a few days later, you talk to the same person and they have a whole new lease on life.”

And the positive effects can extend deep into the family system, he says.

After psilocybin treatment, says Richards, the person with cancer can become a kind of social worker for the family. They’re often far better able to talk about death and loss and even money and family issues than their loved ones. It’s not uncommon after treatment to see the resolution of years-old resentments or grievances that have dogged a family for many years.

Plus, says Richards, the cancer patient often ends up as a kind model to other family members for how to approach death. “They can demonstrate how to live fully — right to the last breath — which is a real gift because those relatives and loved ones have to die someday too, you know.”

At 80 years old, Richards is still in active practice and hopes to spend the rest of his days working with people in end-of-life care.

After the Experience

Psychedelic-assisted therapy does not end with the dosing session. Integration sessions, where you discuss what happened during the dosing session, are a key part of most treatments.

The goal is to help participants absorb and “integrate” their experience. It typically happens over two or more sessions of 60 to 90 minutes with a therapist. In some cases, the therapist may invite a significant other to join in the integration process.

Agrawal’s trial at the Bill Richards center added something new: group therapy. Not only did Bansal meet with his therapist, he also met with a group of three other people in the trial who had their dosing the same day.

The point, says Agrawal, is to try and determine the effect of the group on the therapy. After their private dosing sessions, they come back together to discuss their experiences.

“After the psilocybin, they feel like they’ve been to war together,” Agrawal says. “There is this profound openness and connection. They feel able to share things with each other that they wouldn’t with other people.”

It will take some time to figure out how the group affects the overall outcome, but Bansal thinks it was integral to the success of his treatment.

In fact, he continues to meet regularly with his therapy group, even though it’s long since past the requirements of the study.

Pradeep 2.0

Bansal still has tough days with his cancer. Recently, immunotherapy treatment for his bladder caused side effects — pain, bleeding, fever, and chills — for most of the night. He felt like he was “passing razor blades” when he peed.

“And yet it was somehow OK,” he says. “It was only pain.”

“It’s as if there is a part of me that is watching myself objectively, going through the painful process of treatments saying, ‘It’s all right. I will be with you through this journey, through this experience. Don’t worry.'”

Months after taking that one dose, Bansal still calls it as “the single most powerful experience of my life.”

The change in his mental outlook, Bansal says, was profound, particularly in regard to his cancer.

“I understood that I still had cancer and that it could kill me in a few weeks, or months, or years. But my perspective had shifted.”

Bansal was as surprised as anyone.

“Had somebody told me going into this that I would come out a transformed being or a person with a completely different perspective on life, I would never have believed it.”

He even named his new outlook. “I call it Pradeep 2.0.”

Source: Read Full Article